On the Growing Palestinian Film Culture

Today, we skip the first question, to which we answer in retrospect that Palestinian cinema did indeed exist when the book was first published, and still exists today. In the 1970s, the book, with its contents, diversity, and thoroughness offered a clear and detailed answer to the nature of what Palestinian cinema is (already presuming its existence). Forty years have passed since the book’s first publication, and fifty years since the publication of some of its articles like the “Cinema and the Palestinian Cause” symposium, which was published in Palestinian Affairs Magazine (Shu-un Filastiniyya) in 1972. The article offered important ideas on what Palestinian cinema was like in its early days. However, Palestinian cinema went through a few crises following the exodus from Beirut, when it was interrupted. Today, we move to the second part of the question: “What is it [Palestinian cinema]?” There has been a growth of the Palestinian film industry in the second half of last century. A diverse number of films were made, each of which approached the Palestinian cause diffrently and had filmmakers of different positionalities and frames of reference. This offered the question of “What is it?” a nature similar to what was the Palestinian revolution like.

What was the context in which Palestinian cinema was established, and what is the Palestinian cause today, being an idea of right, rights, freedom, and liberties?

This book presents an early and adequate answer to what Palestinian cinema was and is. Palestinian cinema first emerged in a collective, institutional, and mature form along with this revolution, as a cinema of revolution and of a cause. Through several pages in this book, we may deduce that affiliation with such cinemamaking was a choice - that it was an act of resistance and intellect. We can see this most importantly in the first statement of the Palestine Film Unit, which concludes that “Palestinian cinema is not a geographical affiliation, but rather an affiliation with the struggle of the Palestinian cause.”

The initial purpose of the book, as mentioned by the authors, was to collect different contributions to the discussion on developing the cinema of the Palestinian cause at the time. However, today and for the same reason, the book is considered the most important and comprehensive document in Arabic on the topic, due to its archival nature and research necessity. It is also a direct resource to those who are interested in the cinema of the Palestinian revolution and its parallel alternative and universal Arab cinema. When it was first published, the book aspired to offer an intellectual contribution to a lively discussion. This turned it into a living material from that period, based on which one can understand Palestinian cinema not only during the revolution, but also the concepts, genres, currents, themes, and discussions around Palestinian cinema after all these years, which can still affect Palestinian cinema today.

The book does not only contribute to the discussion on “What is Palestinian cinema?” It is in itself a primary source for defining the nature of cinema today. At the time, Palestinian films and films on the Palestinian cause were seen as films of resistance, revolutionary, and alternative (three traits which are, undoubtedly, shared by all these films, regardless of whether they were made by Arab, Palestinian, or foreign filmmakers, and regardless of whether they were of Palestinian production or not). Today, these films are simply seen as political, regardless of their context or narrative.

Understanding the nature of Palestinian cinema in its early stages, which had the traits I just mentioned, most importantly within that context is it being a cinema of resistance (for which the book offers an expansive resource), helps understand the phases that followed. It also helps understand the reasons behind the transformational changes in this cinema following the exodus from Beirut, beginning in the 1980s all the way into the new century. In that cinema, the image of the Palestinian changed from the fida’i in the cinema of the struggle (which was produced in parallel with other struggle cinemas worldwide), to an image that contradicts with that of revolutionary that rebels against one’s reality. The Palestinian’s image became that of a survivor and a refugee affiliated with a revolution that lost its members, who returns to the refugee camp in confusion. We can realize the political aspect of this post-revolutionary cinema once we understand its political context. It helps us understand what came afterwards, in the first two decades of this century, when the Palestinian cinema entered a new phase in both form and content.

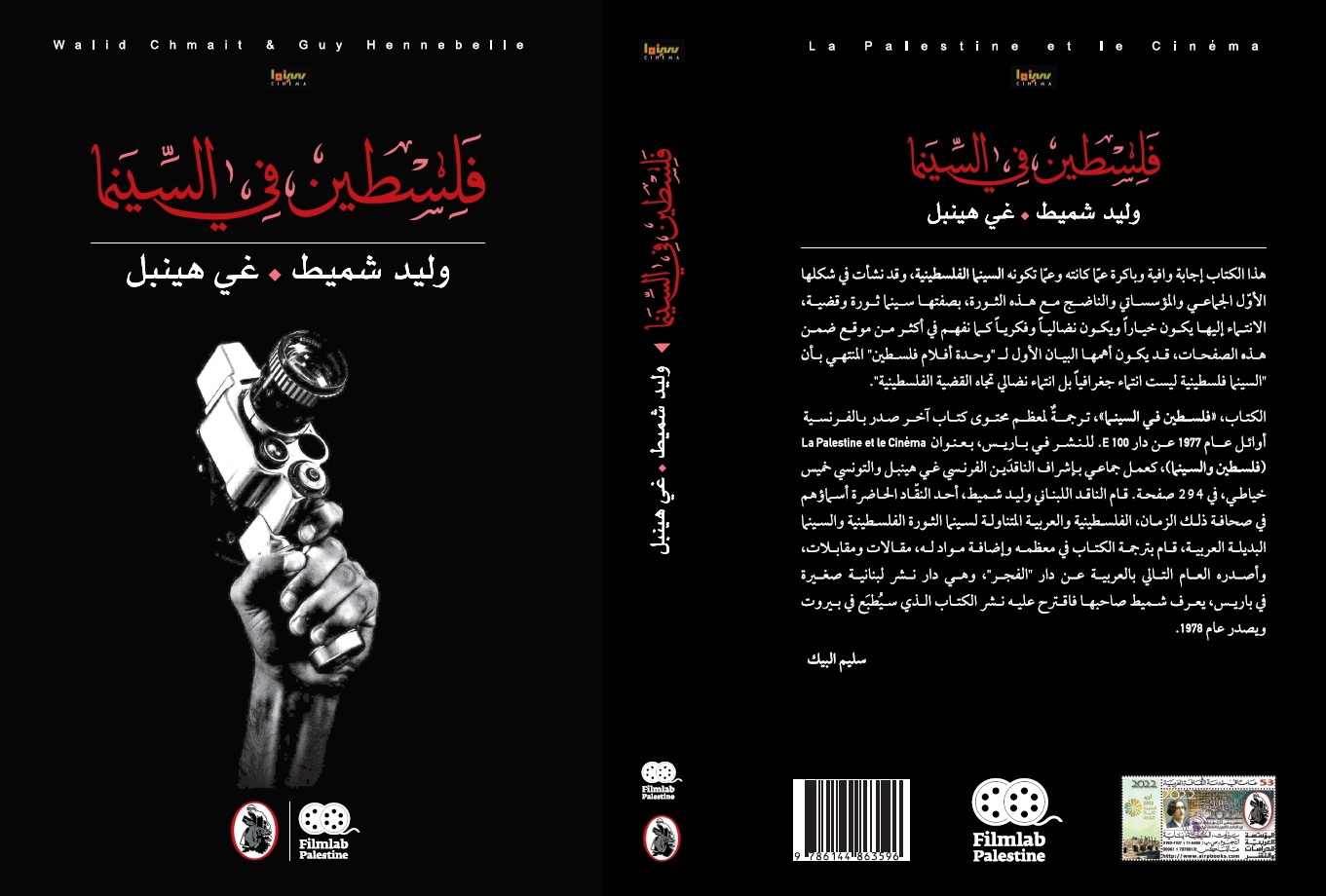

Palestine in Cinema offers a translation of most of what was written in another book, which was published in French in early 1977, by E.100 publishing house in Paris under the title La Palestine et le Cińema (Palestine and Cinema) as a collective work that comprises 294 pages. The book was made under the supervision of the French critic Guy Hennebelle, and the Tunisian critic Khamis Khayati. The Lebanese critic Walid Shamit, who was a prominent critic writing on the cinema of the Palestinian revolution and Arab alternative cinema, in Palestinian and Arab journals, translated most of the book. He also added new sections, including articles and interviews. He published the book the following year with Al-Fajr publishing house in Beirut. Shamit knew the owner of the small publishing house in Paris, so he suggested publishing the book. It was later printed in Beirut and published in 1978.

In 2006, the Palestinian Ministry of Culture, through the Palestinian General Union for Writers, published limited copies of the book with a “second edition” stamp. It did not, however, make reference to the book’s first edition, nor to where and when it was first published, nor to the original French version of the book. This book in your hands is a republication of the edition published by Dar Al-Fajr. Walid Shamit, the author of the book and the owner of its rights, provided us with a copy of the book in Paris. This book is a recollection of the book that was published almost half a century ago. We will not use the terms “second” or “third” edition as the book was not sold out in its first. Rather, we are writing about an edition which was organized and edited by the Palestine Cinema Days, to be published as part of the 9th edition of the festival. We are attaching the book to the special programme, which was put together by the festival in commemoration of the 40th anniversary of the Palestinian exodus from Beirut, in parallel with the main programme of the festival.

There are insufficient titles on Palestinian cinema in the Arab library. We can say that this also applies to books published in other languages. Through republishing this book and making it available to those interested in Palestinian cinema, we open a space for an active critical and intellectual discussion of Palestinian cinema of different times, particularly today. We try to enrich the discussion in the Palestinian cinema scene today by starting from the beginning, from the cinema of the revolution.

Films, screening theaters and festivals are not enough for cinema. Cinema remains incomplete without the local audience’s general film literacy, or the specialized critical film literacy of those working in different aspects of cinema. Cinema is knowledge as much as it is viewership. Perhaps this book can be a step towards enriching the Palestinian cinema culture by building on what came before it and opening new horizons to others.

Saleem Albeik

Paris - September, 2022